by Joan

Several years ago I read Joan Didion’s Year of Magical Thinking, her raw and honest memoir covering the

death of her husband and writing confidant, John Gregory Dunne, and the serious illness of their daughter, Quintana Roo (who recovered but later died).

I always meant to read Didion’s earlier novels and essays, but

never quite got around to it. Then about a month ago, I came across a

fascinating 1978 Paris Review interview with Linda Kuehl, The Art of Fiction:

When asked to clarify what she meant by: “Writing is a

hostile act,” Didion replied, “It’s hostile in that you're trying to make

somebody see something the way you see it, trying to impose your idea, your

picture. It's hostile to try to wrench around someone else's mind that way.

Quite often you want to tell somebody your dream, your nightmare. Well, nobody

wants to hear about someone else's dream, good or bad; nobody wants to walk around

with it. The writer is always tricking the reader into listening to the dream.”

In the interview, Didion said she began typing out

Hemingway’s stories to learn how his sentences worked. “I mean they’re perfect

sentences. Very direct sentences, smooth rivers, clear water over granite, no

sinkholes.” Didion also noted Henry James as an influence. “He wrote perfect

sentences, too, but very indirect, very complicated. Sentences with sinkholes. You could drown in

them.”

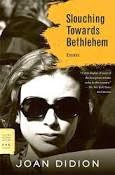

After reading this article I decided I must search out more

of her work. I started with Slouching

Toward Bethlehem, a collection of essays published in the 60s. The audible version was

performed by Diane Keaton, a perfect blend of narrator and author. Occasionally

when listening to an audio book, I find myself rewinding to catch a sentence or

scene I’ve missed. But while listening to these essays, I pushed rewind more often, not because my mind had wandered as sometimes happens,

but because I wanted to hear the brilliance again.

Aside from

the John Wayne article in which he’s very much alive, and perhaps the title

story covering the Haight-Ashbury druggie scene, the essays were surprisingly

relevant and immediate to now. Whether California and its dichotomous

personality and landscape, or New York in the author’s twenties, the essays are

individual yet universal, abundant with literary inspiration. In “On Keeping a

Notebook” Didion shares her thoughts on why a notebook is not a journal. She

jots down snippets of conversations, places and times of random incidents, not

as self-reflection, but as a chance to document how we create our own memories.

One cannot read Didion without wanting to capture some of

her more profound statements, to quote and revisit.

“The impulse to write things down is a peculiarly compulsive

one, inexplicable to those who do not share it, useful only accidentally, only

secondarily, in the way that any compulsion tries to justify itself. I suppose

that it begins or does not begin in the cradle.”

“I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with

the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not.

Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the

mind's door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who

betrayed them, who is going to make amends. We forget all too soon the things

we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike,

forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were. I have

already lost touch with a couple of people I used to be…”

I particularly liked her essay, “On Self-respect.” It seems an

appropriate message for writers who live so close to rejection, but also for recent

graduates who are struggling with what to make of themselves and where they

will land in this world.

“People with self-respect exhibit a certain toughness, a

kind of moral nerve; they display what was once called ‘character,’ a quality

which, although approved in the abstract, sometimes loses ground to the other,

more instantly negotiable virtues.... character—the willingness to accept responsibility

for one's own life—is the source from which self-respect springs.”

“To have that sense of one's intrinsic worth which

constitutes self-respect is potentially to have everything: the ability to discriminate,

to love and to remain indifferent. To lack it is to be locked within oneself,

paradoxically incapable of either love or indifference.”

It turns out, Didion’s style has the flair of both Hemingway

and James: clear and direct, a smooth river with an occasional sinkhole

to drown in. For more on Didion, listen to fascinating podcasts of her NYPL interview or talk with David L. Ulin as part of Aloud, at the Los Angeles Public Library.

No comments:

Post a Comment